Two days before Christmas, Literary Hub posted on its website a text by Gay Talese about his legendary interview with Frank Sinatra and how journalism, new journalism and that line of non-fiction literature have now been distorted. fiction and its counterpart autofiction, the term coined by Serge Doubrovsky, a French literary critic and novelist, but used so much lately in editorial marketing that it almost seems like a reprise of the Latin American Boom, with capital letters of unsubstantiated exaggeration.

Talese is a writer who chisels every sentence. He can take days, weeks to write a sentence. He does not start another until he considers that what is written adheres to what he wants to say to the millimeter. It is repeated that it took 10 years to write 54 pages. A record, but they did not give him the Nobel nor the Guinness.

He refers that as someone who was identified in the 1960s as one of those who popularized a literary genre better known as New Journalism, an innovation of uncertain origin that appeared in Esquire, Harper's, The The New Yorker and other magazines, and with the bylines of writers like Norman Mailer and Lillian Ross, John McPhee, Tom Wolfe, and the late Truman Capote, now admits, without much fanfare, that those pieces of the past—thoroughly researched, creatively arranged , with an innovative style and a groundbreaking and even defiant attitude) are increasingly rare. “They are victims of the reluctance of magazine editors to invest in the rising cost of such writing, much diminished and discarded by the inclination of younger writers not to spend time and energy and do interviews with something numbing: the recorder," he says.

He says that he has been interviewed by writers who use a tape recorder and as he answered the questions, the average interviewer listened, nodded politely and nonchalantly because the tape recorder was still working.

“But what he got from me (and I guess from the other interviewees) is not the insight that comes from deep and dedicated fieldwork like in the old days. It's just the first draft in my mind. A superficial dialogue that too often reduces the job of writing to a circumstantial conversation on the radio, without any depth, to entertain. Very symptomatic of a computerized, impersonalized, fast food-obsessed society. Far from rejecting this trend, most publishers tacitly approve and even encourage it. A faithfully transcribed recorded interview will not face complaints or lawsuits in court from interviewees who, in these times of impulsive litigation, claim to have been misquoted to the detriment of their good name. The high legal fees cause a lot of discomfort and, sometimes, immobility even in the most independent and courageous publishers”, Talese breaks down.

Another reason publishers prefer transcribed tape recorder interviews, complete with clang, is because they allow them to publish acceptable articles from freelance writers who are paid rates well below what they otherwise would – and deserve – writers with greater commitment and better results.

“With one or two interviews and a few hours of recording, a journalist with minimal experience can produce a three thousand word article based on direct quotes. You can earn between five hundred and two thousand dollars, it will depend on how valuable and popular the interviewee is. Of course, it is a fair payment considering the time and skill required, but much less than what they paid for an article of similar content and size when I started writing for these magazines a little over 30 years ago”, he recalls.

He details that in those days the writers he admired spent weeks and months researching, organizing the data, writing and rewriting before the articles were considered worthy of being published in journals. Today our successors spend a tenth of the time on it, and the editors are far less lavish when it comes to investigative spending.

The interview with Frank Sinatra in Los Angeles

He says that in the winter of 1965 Esquire sent him to Los Angeles to interview Frank Sinatra. The singer's publicist had arranged it with the editor of the magazine. “After checking into the Beverly Wilshire Hotel, renting a car, and spending the night in my spacious room poring over a thick packet of Sinatra reference material, along with a succulent steak and a bottle of California's best red wine, burgandy, I got a call from Sinatra's office. My scheduled interview would not be possible.”

Sinatra was very upset by the latest headlines in the newspapers about his alleged mob connections and, furthermore, he had a bad cold that threatened to postpone the taping of an NBC-TV program in which Talese wanted to be present to see Sinatra working.

Sinatra's office told him he might be able to see him when the singer was feeling better. Something else, they confided in him that the interview could be rescheduled, he promised to send them the text before it was published in Esquire.

“After commiserating over the Sinatra cold and the mob news, I very politely explained that my obligation was to honor my publisher's right to be the first to read my work. I asked, in the same tone, if I could call Sinatra's office during the week just in case his health and spirits had improved and he would grant me a brief visit. They told me that they had to call Sinatra's representative, that they didn't promise me anything,” he says.

The rest of the week—after reporting the situation to Esquire editor Harold Hayes—Talese arranged to interview various actors and musicians, studio executives, record producers, restaurant owners, and women they had met. Sinatra through the years.

“I got something from each one. A thread here, a color there, little pieces of a grand mosaic that might reflect the man who for years had been the center of attention and had cast long shadows over the fickle entertainment industry and American consciousness. As I did my interviews, taking them out to dinner or lunch, I accumulated expenses. Including the hotel room and the car, they were over $1,300. Rarely in conversations did he take out a pen or a notebook. If I had had a tape recorder I would not have considered using it."

He had his reasons:

“Doing so would have inhibited the candor of those who expressed themselves with candor and disturbed the atmosphere of trust and camaraderie that I had fostered with my apparently less inquisitive way of research. In addition to my promise that I would not attribute or quote anything they told me without first confirming and clarifying it with them. Verbatim quotations have never gone well with my style of writing, my narrative. Nor with my desire to observe and describe people actively participating in ordinary but revealing situations. I do not confine them to a room and present them in the passivity of a monologue. Since my early days in journalism I have been less interested in the exact words that came out of his mouth than in the gist of what he meant.

“More important than what people say is what they think, even if what they think is more difficult to articulate and requires a lot of reflection and reworking in the interviewee's mind. It is what I try to incite and stimulate while asking and relating. I try to identify with my interviewees and accompany them whenever possible on their commitments, their walks, their aimless pilgrimages before dinner or after work.

“Wherever I am, I try to be present in my role as a curious confidant, a fellow traveler searching within, trying to discover, clarify, and ultimately describe with my words what they are, what they embody and how they think.

There are exceptions, of course:

“Sometimes I take notes. Sometimes one hears a comment, a phrase change, a special word, a personal revelation that must be written down immediately so that part of it is not forgotten. That's when he took out the freedom and said: 'That's wonderful. Let me write it down just like you said it. The person, usually flattered, not only repeats it, but also expands on it. A high spirit of cooperation, almost collaboration, can emerge on such occasions. The interviewee acknowledges that he has contributed something that the writer appreciates to the point of wanting to keep it on paper”.

Talese can take notes without the interviewee's knowledge. Especially when conversations are interrupted and he is momentarily alone. At that time, write down what you consider important in the conversation.

“Occasionally I take notes after the interview is over, when it is still fresh in my mind. So late at night, before going to bed, I sit down and write down in detail what I have seen and heard that day. A chronicle to which I constantly add pages with each day of the research period. The first chronicle consists of four or five single-spaced pages.

“I write down the places where we had breakfast, lunch and dinner (restaurant receipts attached to document my expenses); the exact time, duration, place and subject of each interview; along with the agreed terms of each meeting (i.e. say, am I free to identify the source or am I required to contact that person for clarification or authorization?).

“The chronicle also includes my personal impressions of the people I interviewed, their gestures and physical description, my assessment of their credibility, and my own feelings and concerns as I go through each day. An intimate annex, which now, after almost 30 years, is used for a somewhat autobiographical book that I write. But the original intention of such painstaking writing is to clarify ideas, to reaffirm my own voice on paper after hours of concentrating listening to others and not infrequently as an outlet for the frustration I felt when my research seemed to go wrong, as it certainly did in the winter. 1965 when I couldn't meet Frank Sinatra face to face."

Talese tried to reschedule the interview with Sinatra in his second week in Los Angeles. Because they told him that he still had a cold, he continued to meet with employees of the singer's many companies. His record company, his movie company, his real estate platform, his missile parts dealer, his airplane hangar. He also met people who knew Sinatra, such as his overshadowed son, his favorite tailor in Beverly Hills, and one of his bodyguards. "Also a little gray-haired woman who traveled with Sinatra across the country on concert tours and carried the 60 toupees or toupees in a bag," she said.

“From all those people I collected facts and comments, but what I got at first was not one particular insight or eloquent summary of Sinatra's stature. It was more the awareness that these people working in different places were united in the knowledge that Frank Sinatra had a cold. When I mentioned him in conversations and cited him as the reason for postponing the interview, they nodded and said they knew about his cold and that they knew from his inner circle contacts that he was a difficult man to deal with when he had a sore throat and his nose was running.

“Some of the musicians and studio technicians delayed their recording tasks due to the cold, while others of the 75 team members at their service not only empathized with the effects of the ailment, but also revealed, with examples, how volatile and short-tempered he was all week because he didn't meet his singing standards.

In one night, in the hotel, I wrote in the chronicle:

The next morning, Talese received a call from Frank Sinatra's director of public relations, who complained with an accusatory note:

“I hear you've been meeting and having dinner with Frank's friends.”

Talese replied flatly: “I'm doing my job.” And without giving her time to react, he asked her with absolute familiarity: "How is Frank's cold?"

The response was more than circumstantial: “Much better, but still not enough to talk to you. If you want you can come with me tomorrow afternoon. Frank will try to record part of his special from his NBC special. I look for him at the hotel at three”.

He suspected the relacionista intended to keep a closer eye on him, but he was pleased to be invited to the taping of the first segment of the hour-long special that NBC-TV was scheduled to air in two weeks entitled “Sinatra, the Man and His music".

The next afternoon, Talese recounts, the dapper publicist picked him up promptly and courteously in a Mercedes convertible. With a square jaw, auburn hair, and a deep tan, he sported a three-piece trench coat suit. Talese complimented him as soon as he got in the car. He was pleased to admit that he had gotten it at a special price at Frank's favorite tailor shop. “On the way, the conversation was restricted to clothes, weather and sports until we got to the NBC building. In the white concrete parking lot were thirty other Mercedes convertibles and several limousines in which the drivers, wearing black caps, were trying to sleep.

They entered the building and he followed the publicist down a hallway that led to a huge studio dominated by a white set and white walls. Dozens of lamps and lights hung everywhere. It looked like a gigantic operating room.

After two hours in the studio, in which Sinatra's publicist didn't move from him even when he went to the bathroom, Talese recalled precise details of what he had seen and heard on the recording. He added to his chronicle:

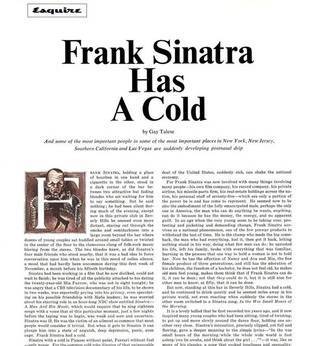

Esquire titled the piece "Frank Sinatra Has a Cold" and it appeared in the April 1966 issue. It is now included in a Dell paperback collection called Fame and Obscurity. Talese says that, although she never had the opportunity to sit down and talk alone with Frank Sinatra, this "glitch" is perhaps one of the strong points of the article.

“What could or would have said (as one of the most guarded public figures) that would have revealed him better than an observant writer who watches him in action, sees him in stressful situations, listens to him, and stays out of his life ? This method of long and careful listening and describing scenes, which gives insight into an individual's character and personality, a method that a generation ago came to be called the New Journalism, was, at best, truly strengthened by the principles of "Old Journalism": tireless fieldwork and fidelity to factual accuracy.

“Although time consuming and financially expensive, the research was what marked my Sinatra article and dozens of other journal articles I published during the 1960s. During this period there were other writers who were doing even more research than I was, particularly at The New Yorker, one of the few publications that could afford it, and still today chooses the high cost of sending writers on trips and allowing them the time. as necessary to write with depth and understanding about people and places.

“Among the writers of my generation at The New Yorker who epitomize this dedication are Calvin Trillin and the aforementioned John McPhee. The most recent example in Esquire was the article on former baseball star Ted Williams, written by Richard Ben Cramer, a 36-year-old street-kicking reporter whose acute listening skills were obviously not dulled or corrupted by a tape recorder's plastic ear."

Also read on Cambio16.com:

Subscribe and support us "For a more humane, just and regenerative world"

Thank you for reading Cambio16. Your subscription will not only provide accurate and truthful news, but will also contribute to the resurgence of journalism in Spain for the transformation of conscience and society through personal growth, the defense of freedoms, democracies, social justice, conservation of the environment and biodiversity.

As our operating income is under great pressure, your support can help us carry out the important work we do. If you can, support Cambio16 Thank you for your contribution!